Tamara Dean

Amidst Australia’s awe-inspiring vistas, Tamara Dean stands as a visual poet, writing verses not with words, but with lenses and

A few weeks ago, 0→1 had the opportunity to engage in an open discussion with Harry Woodrow, an innovative British artist and designer currently living in Stockholm, Sweden.

Harry Woodrow is a visionary who excels at discerning the extraordinary in the seemingly ordinary. He challenges conventional perspectives, offering fresh and radical ways to perceive and interact with the world. In doing so, he not only battles his own cynicism but also finds a unique kind of sanity in a world increasingly characterized by uniform tastes and controlled environments.

Read on!

↑ ( 2 above) — Gethin Wyn Jones →

What sparked your career in art and design?

My dad is an artist, so art has always been around me. It’s unspoken; it’s just there. I knew nothing about graphic design until I took a foundation course at Central St. Martins in London, my hometown. I originally wanted to study painting. However, I quickly realized its difficulty. At 17, I didn’t have much experience to draw on, so I didn’t know what to paint. Graphic design was easier in a sense; it began with a brief. This brief either could align with my interests or I could ignore it. Yet, it provided some sort of impetus to my thought process.

Also, I remember during that year I bumped into my friend Will (→) on the bus at Elephant & Castle.I knew him through skateboarding and really looked up to him. He was already enrolled in the graphic design program at CSM. We bonded over some Dutch techno records we both had, which led us to discuss music and other topics. He told me, ‘Oh you should come and do graphics, it’s great, you can do anything you like and call it graphic design, you can make paintings’.

This, combined with my low regard for the fine art students in my course, pointed me in one direction. I secured a spot at CSM on the degree course, where some truly inspiring teachers shaped my path. An important one was Paul Neale from Graphic Thought Facility ( → ). I’ve been in graphic design ever since. My journey began with a brief but impactful period at Michael Nash Associates ( → ). Later, I co-founded Multistorey ( → ) with Rhonda Drakeford ( → ) in 1997.

When did you realize you were more into arts than graphic design?

Over the years, I’d occasionally paint or decide to photograph an object. These acts weren’t particularly thought-out, yet always very satisfying. For a long while, I harbored a misguided belief in design purity. I thought I should only work on ‘real’ briefs and saw personal projects as self-indulgent wank. From 2000-2010, many graphic designers created their own work, but it was mostly shit. It was mostly things like screenprints of fixed-gear bikes, a scene I had little interest in joining.

In 2010, we shifted the studio’s focus as Rhonda launched Darkroom ( → ). I continued with individual and joint design projects under Multistorey, yet found myself grappling with disillusionment and self-questioning. Design commissions had lost some of their previous allure for me. Clients wanted streamlined aesthetics, leaving little space for the playful ideas I enjoyed making.

I needed another, a very personal outlet for my thoughts. Overcoming my self-defeating beliefs about my own expression took time and many conversations with friends. Fabienne Hess ( → ), a fellow graphic designer turned artist, was especially encouraging. Ultimately, she helped me embrace my inner artist, which I’d always threatened to be.

Another thing worth saying is that after I’d come to terms with the struggle and successfully managed to split myself into two parts, artist and designer. I began to appreciate making graphic design again but in a different way than before. I wasn’t trying to shoehorn unwanted ideas into every project, ideas that would only really be there for my own benefit — it’s become more of a craft for me than something that needs to satisfy me completely. I’m active with Multistorey to this day and continue to make work that I enjoy and of which I’m very proud.

Did your graphic design education shape your style or identity? How was that journey?

I can’t say for sure, but experimenting with various materials and processes has been invaluable. Learning to collaborate effectively with suppliers and fabricators has been key. Sometimes, I even had to persuade them to use their expertise in new, unexplored ways.

Also, I tend to work in a project structure — I don’t have a specific material or process that I endlessly explore. That probably stems from my design experience, but then again it could be just how my mind works and explains why I was initially drawn to design.

Any other experiences that shaped your artistic journey?

Relocating from London to Stockholm in 2015 was very healthy for me, was born a London and had never lived elsewhere. The move offered a different scale of life and a slower pace, giving me the room—physically and mentally — to actually make work. In London, I had grown cynical and had established a reputation. Landing in a city where I was unknown brought fresh inspiration and the unique viewpoint of an outsider.

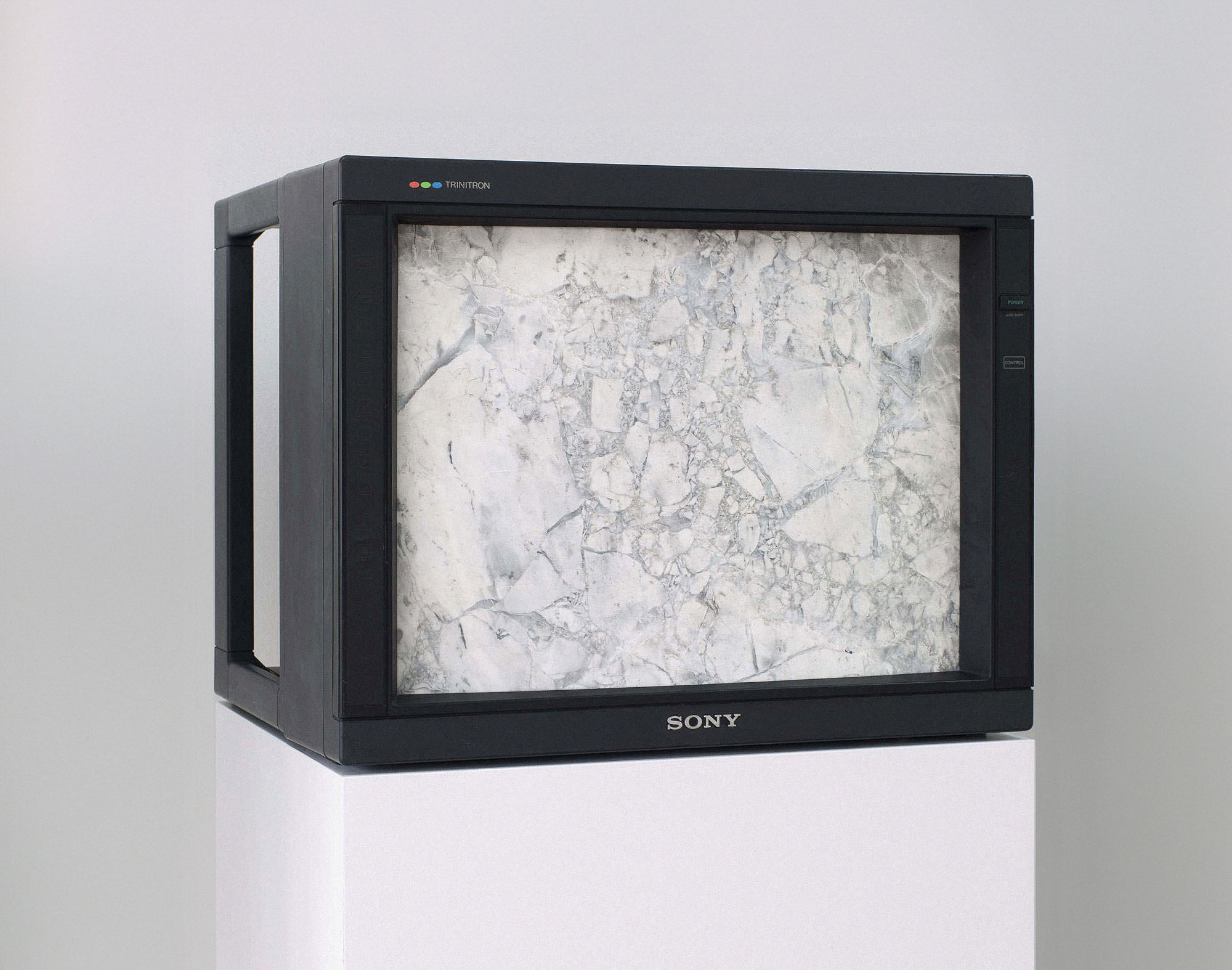

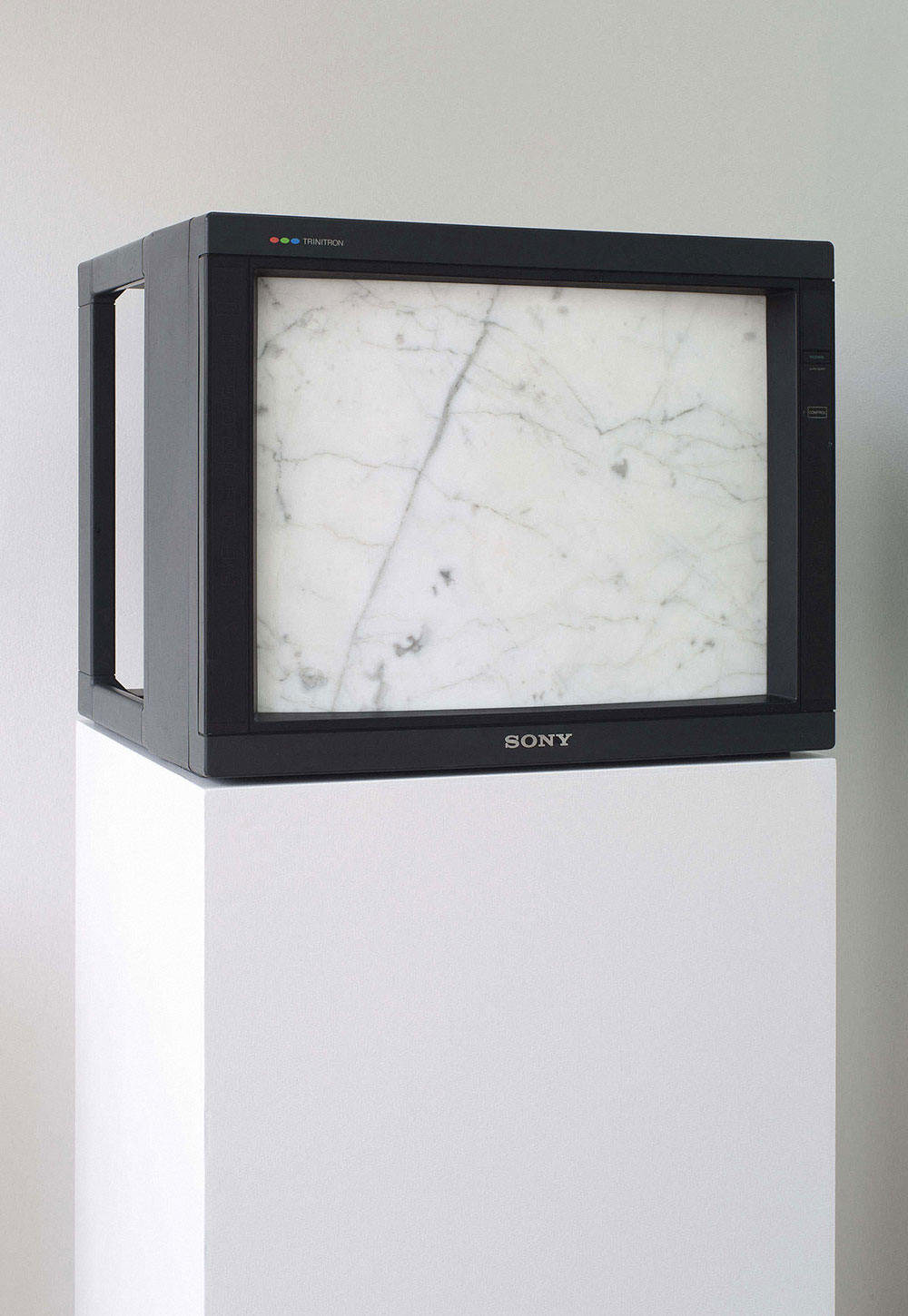

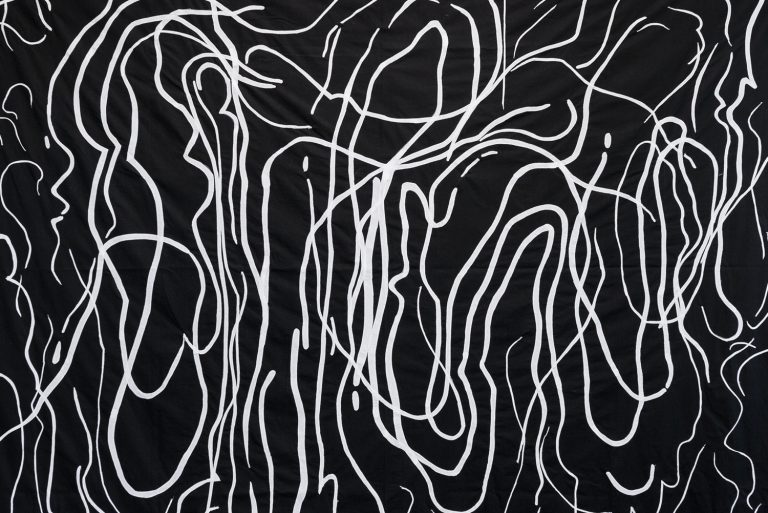

↑ ( 3 above) — Harry Woodrow, Video Art / 2016

What influences or inspires your work the most?

Everything.

What’s the initial spark that gets your project off the ground?

Generally, my projects start by me noticing or finding something, behavior, or phenomenon impossible to ignore. This new insight or knowledge will gnaw away at me for a while, half-buried until I figure out a way of using it or illuminating it.

I frequently find myself wondering, ‘Has nobody else ever thought about how incredibly strange _______ is?’ I then explore different methods and languages of expression to bring my feelings and thoughts about whatever ‘_______’ is, to life, in an interesting and satisfying way.

How do you pick the medium for each project?

It’s hard to say, but it feels like a natural process, I suppose it’s a combination of what I feel to be appropriate and what I’d like to play with at the time.

Do you have a mission or underlying idea that guides your work?

Not a very clear one, I don’t think so. I enjoy making the familiar unfamiliar and also making people think more about what they do, and why and how they do it. But above all, I need to keep myself interested and challenged, or I can easily fall into disillusionment and cycles of gloom.

Your #Selfies series has been ongoing since 2014 and offers a unique perspective on self-portraiture and social media behavior. Could you share the initial inspiration or the ‘spark’ that set this project into motion?”

The Selfies came from a braiding together of two different strands of thought that I was trying to resolve around 2013/14. The main one was my bafflement at the rise of selfies in general and on Instagram in particular. I just thought that it was so incredibly boring to just see someone’s face over and over again. I’d much rather know what they were looking at and what they thought about it. The trend escalated to a point where I’d unfollow people for excessive selfie posts.

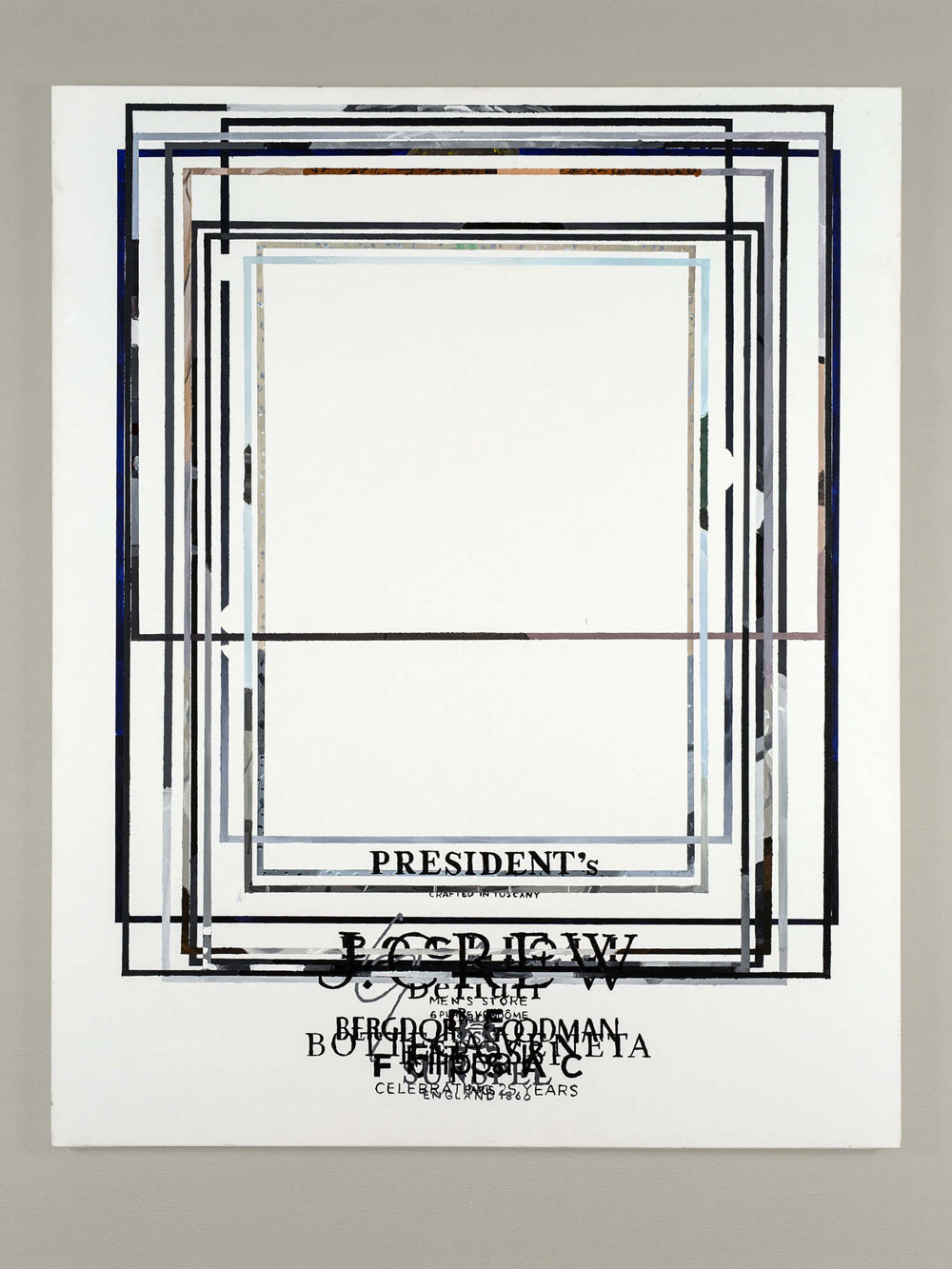

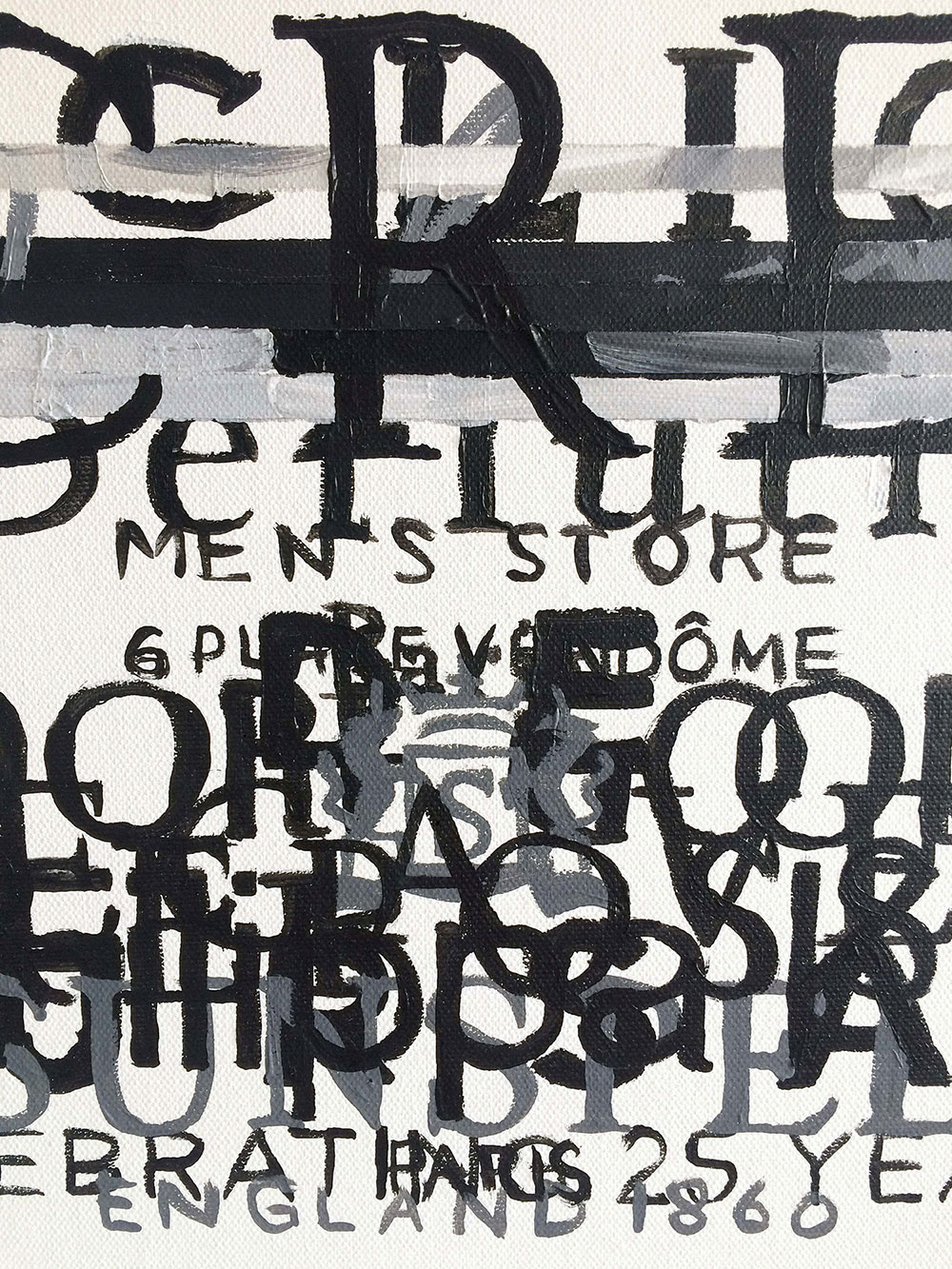

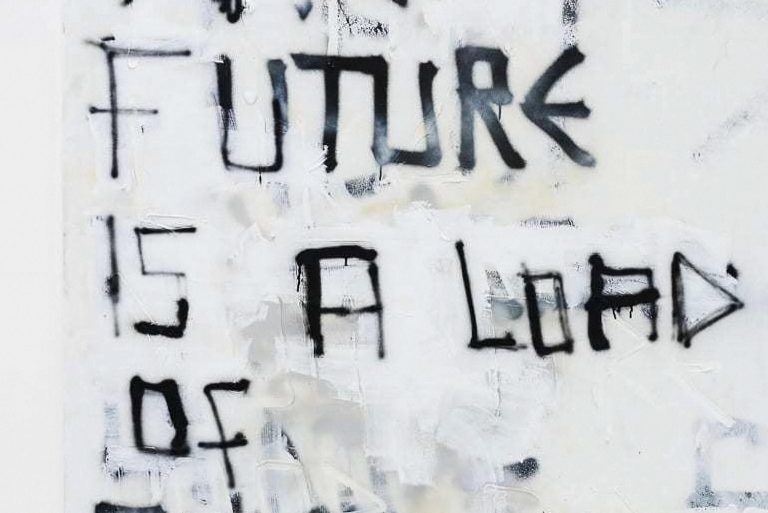

↑ (2 above) — Harry Woodrow, Protest Painting (Fantastic Man no.22) / 2015

↑ (2 above) — Harry Woodrow, Protest Painting (Gentlewoman no.12) / 2015

(As an aside, I often [only half-jokingly] say that the introduction of the iPhone’s front-facing camera in 2010 marked the beginning of the end of humanity. Once that opportunity was offered to us all to stare longingly into our own faces all day, we as a species could be ruthlessly and cynically exploited at a level beyond anything that had come before. We would hurtle towards our own extinction while obliviously hypnotized and tortured by our own vanities and insecurities.)

And also, around the same time, I found the emerging ‘art selfie’ both fascinating and repulsive. In every gallery I visited, people were taking selfies next to or in the reflection of the shiny surfaces of art. Initially, museums deemed this behavior vulgar and discouraged it. Yet, desperate for publicity and foot traffic, they embraced the trend. Before long, every big exhibit had an official hashtag and an unstated but obvious selfie room. My feed was swamped with people I knew, standing in Yayoi Kusama’s mirrored rooms or amidst Martin Creed’s white balloons at the Hayward.

It seemed like 90% of Facebook profile pics were snapped in an Olafur Eliasson installation. This got me thinking and trying to work out if I could make art so captivating that people couldn’t resist whipping out their phones and taking a selfie. Yet, for some unknown reason, the art would defy photography — it would be unphotographable.

Clearly, I never figured out how to make this happen, but the idea continued to bubble in my mind. Then In November 2014, my friend Ben Branagan ( → ) and I had a joint exhibition, Solid State, at London’s Coleman Project Space.

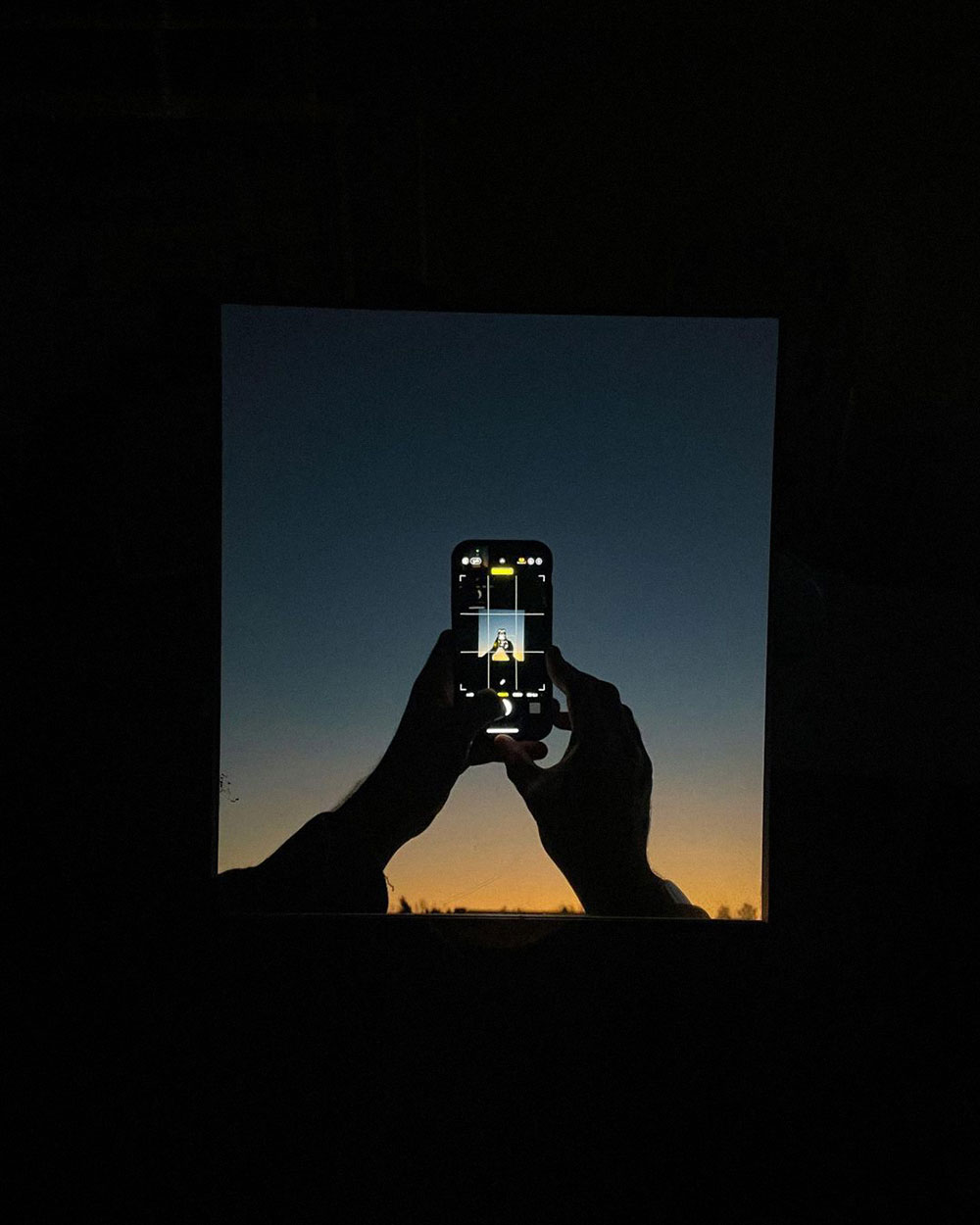

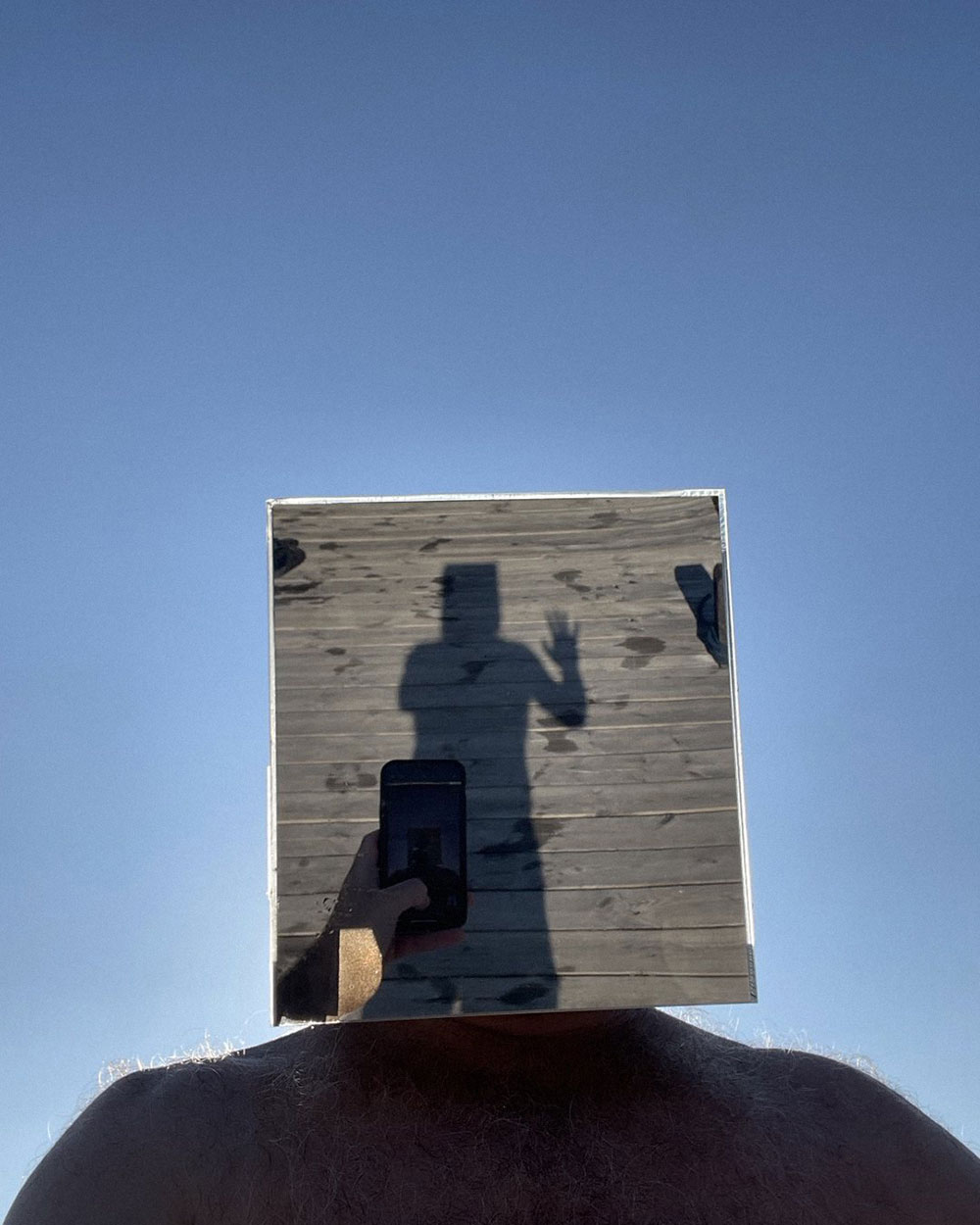

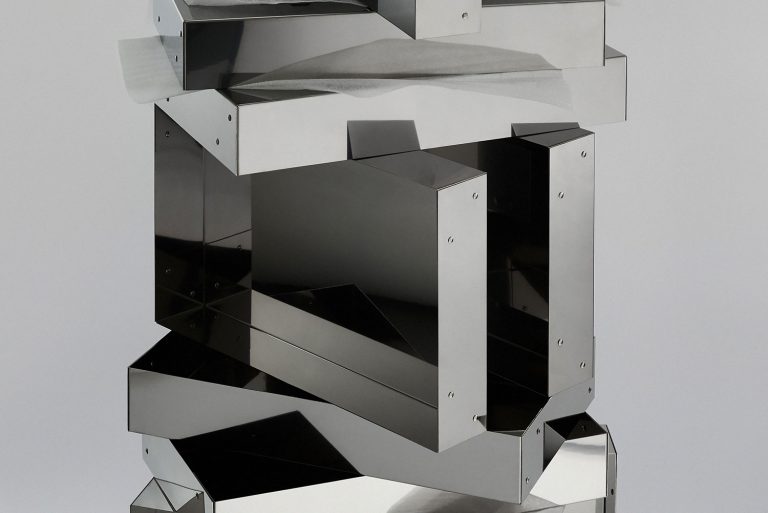

While working towards that show, my unresolved art/selfie thoughts coalesced into the construction of a cubic helmet made from a two-way mirror. I could see out, but any person or lens looking at me would only see the reflection of themselves and their surroundings. So when I aimed my front-facing camera at my helmet-obscured face, the iPhone screen would record an image of itself, looking back at itself, in an infinite loop of reflective feedback. I exhibited 9 of the photographs in the exhibition, then soon realized that Instagram was the project’s natural home.

In the feed, the mass of images becomes relentless, strange, and deliberately boring. The ‘square within a square’ in lieu of a face highlights the bizarre, unnerving nature of selfie-centric Instagram accounts. But also, the project also helped me resolve different facets of my personality. I dislike having my photo taken and find self-promotion and oversharing embarrassing. However, I’m also quite extroverted and very interested in clothes and self-image. The project let me embrace all of those things. It allowed me to be fully present yet anonymous, narcissistic but still concealed.

↑ (4 above) — Harry Woodrow, Selfies / 2014 – ongoing

As someone who’s navigated the art world, do you have any hard-earned wisdom to offer emerging artists and designers? Was there a piece of advice that was a game-changer for you?

I’m not sure, but an old friend Fritz once told me something that’s stayed with me: ‘You are an artist, therefore it is your duty to show the world what you see.’

This helped me as I wrestled with calling myself an artist. Back then, I was extremely shy about showing my work, and Fritz’s words helped me push past some barriers.

To wrap things up, could you give us a sneak peek into your upcoming projects? What’s next on your creative horizon?

For the past few years, I’ve been collecting realtor signs, ads, and flyers in Stockholm for an ongoing project. It might never become an exhibition or installation, but it amuses me, and I plan to compile a book this year. Since my son’s birth in 2017, I’ve returned to painting, starting a series on jacuzzis. Let’s see where that takes me. All the while, the selfie project continues.

Amidst Australia’s awe-inspiring vistas, Tamara Dean stands as a visual poet, writing verses not with words, but with lenses and

Forever Studio, based in the Netherlands, searches for unfamiliar combinations in autonomous and commercial design. Launched by Bienke Domenie &

Originally from Örebro, Sweden, artist Tobias Bradford now splits his time between Stockholm and London. His work examines the gray

Richie Culver is a self-taught artist originating from a working-class background in Hull, Northern England. Despite having minimal artistic exposure

Born in Rhenen, Netherlands, the dynamic artist Riëtte Wanders has anchored her creative pursuits in Amsterdam. The sheer magnitude of

Thomas van Rijs, an alumnus of the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, now operates from his Amsterdam base.

Magali Reus’ sculptures are accumulations of images and things. She draws on objects she finds around her, recombining them into

Henri Wagner’s art is a captivating blend of contrasts. His pieces exude a rough, brutal energy, yet simultaneously convey a

Manon Pretto operates amidst the lively streets of Paris and against the historic backdrop of Clermont Ferrand. Her thought-provoking works

Independent Art & Design Gallery 0→1 © 2024

Stay in the loop with 0→1. Join our email list for the latest news, artist highlights, and first dibs on our exclusive collections. Dive into the art world with us — curated, simplified, and personal.

(We respect your inbox. Our updates are curated for value, and you can unsubscribe anytime. No spam, just art.)

We use cookies to improve your browsing experience; details in our Privacy Policy →